MARS: LOG

The story of Dazzle Camouflage is a fascinating one…

The advent of the torpedo during the First World War would change naval warfare for ever.. The sheer bulk of the vessels (together with the copious fumes they spewed out..) meant that they became easy targets for the German U boats.

By 1917, the Allied warships and merchant vessels were being sunk at a rate of over 20 a week.. urgent action was needed..

Various ideas were floated, from the outlandish (disguising ships as icebergs, whales or islands) to covering ships in reflective mirror-like cladding.

Zoologists John Graham Kerr and Abbott Handerson Thayer both approached the Admiralty separately, with proposals for using ‘disruptive colouration’ (as seen on some land animals such as zebra and jaguars) where visual confusion would ‘greatly increase the difficulty of accurate range finding’. But this idea was rejected as eccentric..

The second suggestion offered was of ‘counter-shading’, a technique of inverted shading, which in theory would obliterate the form of the ship upon the sea. This idea was briefly adopted, but its success was inconclusive and it had limited support.

The vorticist artist Edward Wadsworth was a prominent figure in the team (photo first appeared in the New York Herald, now in the National Gallery of Canada; source: Camoupedia)

It was ultimately illustrator, poster and marine artist Norman Wilkinson (then a Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve) who had the drive and the charisma to motivate the Admiralty into adopting the idea of ‘disruptive camouflage’, an idea previously ridiculed as outlandish..

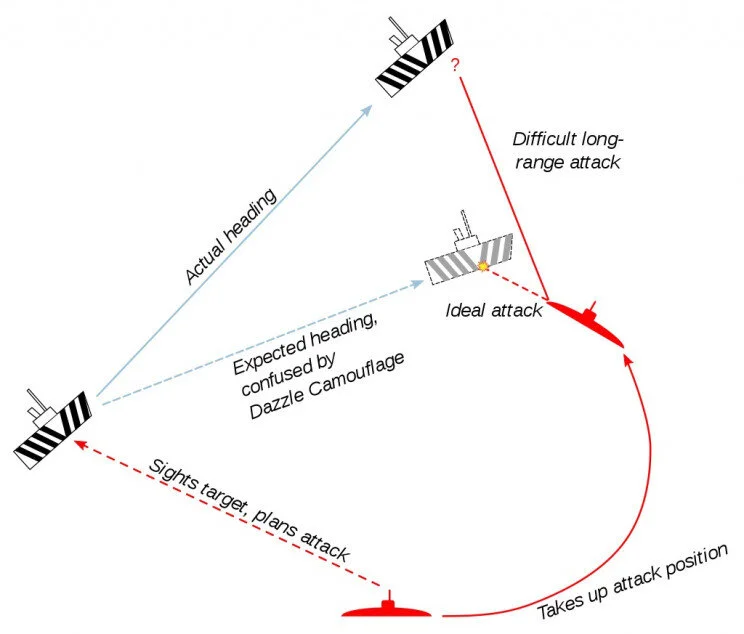

His take was a lot bolder.. Accepting that vessels could never be disguised, the aim was to create as much visual confusion as possible. By applying a cornucopia of contrasting patterns and colours to the ships, it became difficult for the enemy to discern the shape and class of ship, as well as its speed and course. This meant that trying to calculate the trajectory for a torpedo (typically from a distance of around 1.5 miles away) became very difficult, and the slightest misalignment could mean the difference between being hit or not..

Illustration Credit: Norman Wilkinson (source: Encyclopedia Britannica)

The model room at the Royal Academy where patterns could be tested before application (source: Royal Academy)

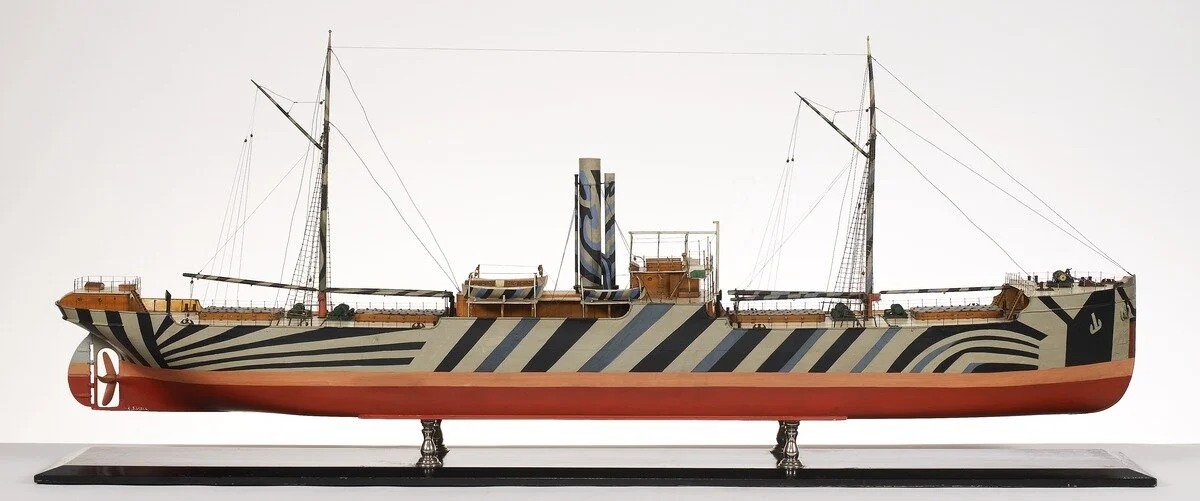

The pattern schemes were first tested on models and viewed through a periscope in a specially built model room. If considered successful, the designs would be sent down to the docks and applied to the designated ship.

U-Boat Commander at the Periscope (Photo Credit: Unknown of German origin; source: Wikipedia)

Diagram describing torpedo trajectories (Author: Ian Alexander)

Artists at work in the Dazzle Camouflage Unit (source: unknown photographer, Royal Academy)

So, by order of the Admiralty and under total secrecy, a team of artists was quickly put together under the leadership of Wilkinson. Based at the Royal Academy School of Art in London, almost all of the student artists were women (as most of the men had been conscripted into the army). They were joined by other leading artists, sculptors and set designers of the day, notably Edward Wadsworth, a prominent exponent of vorticism.

Model of vessel in Dazzle Camouflage (source: Museum aan den Stroom, Antwerp)

HMS Badsworth (credit: unknown photographer; source: Imperial War Museums collection)

No two ships were painted the same.. this was so the enemy would not be able to identify vessel types by the paintwork applied. This led to a profusion of designs and patterns, and the technique was subsequently adopted by other navies.

But.. did it actually work? Post war, the Admiralty tried to analyse the shipping loses suffered, but there were too many factors involved that made it impossible to draw clear conclusions..

Despite this uncertainty, the Dazzle paint scheme was put to use again in WW2, though possibly with less success due to improved rangefinders, aircraft and the use of radar..

HMS Kildangan (credit: unknown photographer; source: Imperial War Museums collection)

USS West Mahomet (credit: unknown photographer; US National Archives)

SS Alloway (credit: unknown photographer; US Naval Historical Center)